A Taste Memory Brought to Life by a Grandmother's Kimchi Recipe

My first taste of kimchi was a revelation…salty, acidic, crunchy, and searingly spicy with the heat from Korean red chiles. I still salivate at the memory of it.

It was made by the mother of my host family in Daejon, South Korea, having fermented in loosely covered clay pots, called onggi, on the flat, exposed roof of their home alongside other mysterious concoctions that drew my curiosity with their richly funky, exotic smells, aromas that were as foreign to my middle-class American palate as tuna noodle casserole and Swiss steak would be to my host family.

I seem to recall the family eyeing me suspiciously as I lifted the chopsticks containing that first bite to my lips, not sure how the big American girl they'd taken into their home might respond. Would she scream? Gag? Run out of the room?

They were probably relieved, if maybe a bit disappointed, that none of those happened, though I remember my lips burning by the end of the meal of fish, wok-seared greens and kimchi. It helped that there was plenty of rice and traditional scorched-rice tea (sungnyung) to help mitigate the fire of the chiles, but I was intrigued.

Since that college trip I've been wanting to recreate the taste that was almost literally seared into my memory 40 years ago, and my experiences with fermentation made me pretty confident I could do it without killing or sickening my friends or family.

So when I found out that my friend Denise was willing to help me make it from the recipe her sister had transcribed from her mother Betty Ann's recipe—one that Betty Ann had learned from her mother, Annie—I was all in. (Read the story of Annie Mah's odyssey and get her recipe for gochujang.)

It began with Denise and I making a trip to one of the city's many large Asian supermarkets to get the coursely ground Korean red peppers, or gochugaru, that is the critical ingredient in kimchi, one that cannot be substituted if your goal is to make the real deal. I'd already picked up the Napa cabbage, daikon and carrots, my preferred mix of vegetables—though the recipe just calls for five pounds of whatever suits your tastes.

Remarkably simple, Denise's family recipe is fairly mild as kimchi goes, confirmed when her relatives sampled my second attempt in which I'd upped the cayenne quotient, making it more like the version I'd had in Korea. Mind you, they liked it, but as her Aunt Else said afterwards, clapping me on the shoulder, "You make it like a Korean would!"

High praise, indeed!

Kimchi (Kim Chee)

Adapted from Betty Ann della Santina's recipe by her daughter, Cynthia Forsberg.

For the brined vegetables, any of the following, about five pounds total:

Daikon, shredded or chunked

Napa or green cabbage, chunked

After brining the vegetables above overnight, add as many of these as you want:

Green onions, sliced in half or quarters lengthwise, cut crosswise in 2 to 3-inch lengths

Yellow onions, chunked

Carrots, shredded

For the paste:

1/2 c. fine to medium crushed Korean red pepper flakes (gochugaru)

3-inch piece ginger peeled and grated (with juice)

5-7 large juicy garlic cloves, crushed

2-3 Tbsp. shrimp powder, shrimp paste, or fish sauce, or a combination

1-3 tsp. ground cayenne pepper or red pepper flakes (optional, depending on your heat tolerance)

2 tsp. sugar

1/2 c. water (only enough to make into paste)

Soak cabbage and daikon in brine of 1 c. salt mixed in one gallon water for 14-24 hours, making sure they stay submerged in the brine. Do this by placing a plate on top of them or half-filling a gallon zip-lock bag with water and placing that on top of the vegetables. The next day, rinse thoroughly in cold water. Drain vegetables and press out most of the remaining water.

Mix together red pepper (gochugaru), grated ginger, crushed garlic, shrimp powder (or fish sauce), cayenne (if using) and sugar in a large bowl with just enough water to make a thick paste.

Add brined and cut vegetables to the paste and mix thoroughly. Press into clean wide-mouth quart (or pint) jars. Press down firmly, allowing 1" space at top, and close the lid tightly, allow to ferment at least 24 to 36 hours on the counter.

[Fermentation time can vary depending on temperature and other factors. I allowed mine to sit in the basement for 5 to 7 days, and started to taste it after the third day until it had developed the "funky" taste I wanted. - KB]

Store in refrigerator.

Get Denise's grandmother's recipe for gochujang (kojujung) and the family's Greek dolmathes (stuffed grape leaves).

This is the time to buy the best eggs you can get, so don't settle for store-bought eggs that may be up to a month old. (And be forewarned: their extraordinary flavor and freshness might just convince you they're worth the price to use all the time.)

This is the time to buy the best eggs you can get, so don't settle for store-bought eggs that may be up to a month old. (And be forewarned: their extraordinary flavor and freshness might just convince you they're worth the price to use all the time.)

Sarah specializes in fermented vegetables from sauerkraut to salsa. Fermenting gives food a sour flavor without any added acid, which differs from pickling, which involves putting food into an acidic brine. Fermenting is a healthier and, in our opinion, tastier way to preserve vegetables such as cabbage. Sarah makes several delicious krauts so we asked for her recommendation. Market Master Ginger Rapport was leaning toward her Caraway Sauerkraut because she loves the hint of onion that Sarah adds to the mix. However she changed her mind at Sarah’s urging and instead picked up a jar of Fermented Leeks with Black Pepper.

Sarah specializes in fermented vegetables from sauerkraut to salsa. Fermenting gives food a sour flavor without any added acid, which differs from pickling, which involves putting food into an acidic brine. Fermenting is a healthier and, in our opinion, tastier way to preserve vegetables such as cabbage. Sarah makes several delicious krauts so we asked for her recommendation. Market Master Ginger Rapport was leaning toward her Caraway Sauerkraut because she loves the hint of onion that Sarah adds to the mix. However she changed her mind at Sarah’s urging and instead picked up a jar of Fermented Leeks with Black Pepper.

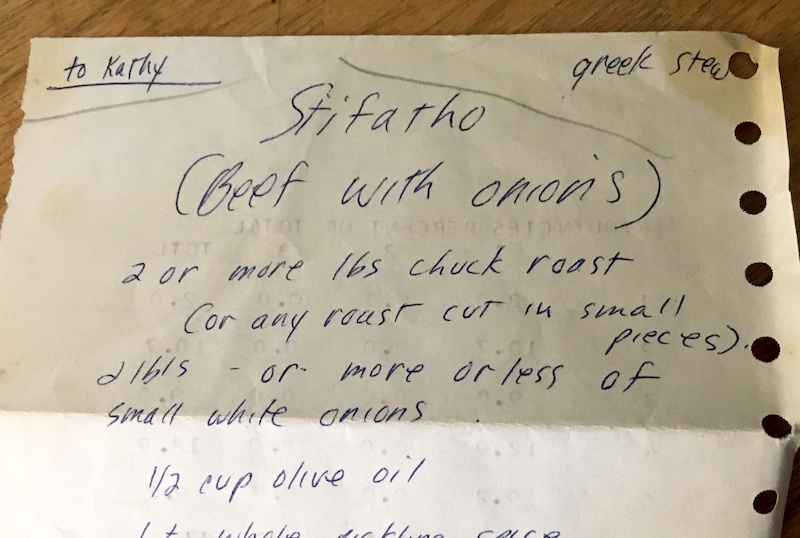

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family.

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family. So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.

So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.