This is my second contribution to Civil Eats' monthly series of profiles of farmers and ranchers who are changing our food system for the benefit of our communities, our health and the environment.

Fourth-generation rancher Cory Carman

holistically manages 5,000-acres

which serve as a model for sustainable meat operations

in the Pacific Northwest.

When Cory Carman returned in 2003 to her family’s ranch in remote Wallowa County in eastern Oregon with a Stanford degree in public policy in hand and a stint on Capitol Hill under her belt, her intention was to stay for the summer, helping her uncle and grandmother with ranch work while she looked for her next job working on public policy. By that fall, though, it was obvious that if she left, the ranch wouldn’t be there for her to come back to.

“They were the only ones left on the ranch,” she said, recalling the heartbreaking specter of how hard her uncle and her grandmother, who was then in her 80s, had to work to barely scrape by. “I think I felt the weight of what they were trying to hold together, and I thought how unfair it was for me to expect that they could just keep it together until I came back someday.”

So she decided to stay.

Carman Ranch began as a few hundred acres Carman’s great-great-grandfather Jacob Weinhard—nephew to the legendary Northwest beer brewer Henry Weinhard—bought for his son Fritz in the early 1900s. Under Carman’s watch, the operation now spans 5,000 acres of grasslands, timbered rangeland, and irrigated valley ground nestled against the dramatic peaks of the Wallowa Mountains. Hawks, eagles, and wildlife greatly outnumber people in this isolated northeastern corner of the state, originally home to the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of the Nez Perce tribe.

Distinct from most cattle operations in the U.S., Carman’s cattle are 100 percent grass-fed well as grass-finished. (The term “grass-fed” is not regulated, so it can mean that animals have only been briefly pastured before they’re sent to a factory feedlot to be finished.) The ranch primarily produces cattle and pigs, which it mostly markets to wholesale accounts, though it sells a lesser amount of meat as “cow shares”—or quarters of beef ranging from 120 to 180 pounds purchased directly by consumers.

Equally if not more important to Carman, however, is the focus on what she calls the “holistic management” of her land. This involves constantly moving the cattle and paying careful attention to the rate of growth of the animals and grasses. By this system, the steers select the forages they need to grow and gain weight, and the grasses get clipped, trampled down, and fertilized with manure, resulting in fields that are vibrant—they retain water, resist drought, contain abundant organic matter, which contributes nutrients and carbon, and are highly productive without the addition of fertilizer.

Equally if not more important to Carman, however, is the focus on what she calls the “holistic management” of her land. This involves constantly moving the cattle and paying careful attention to the rate of growth of the animals and grasses. By this system, the steers select the forages they need to grow and gain weight, and the grasses get clipped, trampled down, and fertilized with manure, resulting in fields that are vibrant—they retain water, resist drought, contain abundant organic matter, which contributes nutrients and carbon, and are highly productive without the addition of fertilizer.

Amanda Oborne, vice president of food and farms at Ecotrust, a regional nonprofit organization working on social, economic, and environmental issues, said Carman inspired Ecotrust’s food system work by helping her understand the challenges of creating local beef and pork markets, the complexity of scaling an agricultural business with integrity, and the importance of grasslands and large grazing animals in fighting climate change through carbon drawdown.

Oborne remembers Carman walking her around the fields of the Zumwalt Prairie, a preserve owned by the Nature Conservancy that is on the western boundary of the ranch, and picking at blades of bunch grass as she explained how the native species create pockets of nutrition for migrating birds through the winter, and how the long, perennial roots scaffold a whole cathedral of structure and life under the soil.

“It’s Cory’s ability to tell these stories, to explain the flaws of the dominant system without imbuing judgement or animosity, and to partner across every divide—be it age, gender, class, political philosophy, or hometown—that makes her such an effective and innovative thought leader,” Oborne said.

Introducing Holistic Management

Within a year of returning to the ranch, Carman met and married her husband, Dave Flynn (the couple have since divorced), and started a family, which includes three children, Roan and twins Ione and Emmett.

With a fifth generation of the family living on the ranch, the challenge became not just figuring out how to maintain her family’s business and regenerate the land, but how to leave a viable legacy to pass on to her children.

“You don’t have a ranch so that you can sell it and retire; you have a ranch so you can pass it on—that’s sort of in the DNA,” Carman said. “It’s what gets priority, and [you] grow up knowing that there’s something more important than all of you as individuals.”

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.

“It was the fertilizer era,” Carman noted of her uncle’s initial resistance to the idea of leaving forage in the pastures. “It’s like in those first few decades when fertilizer worked really, really well. You could just take everything off of the land that you could possibly grow and sell it—and then pour more fertilizer back on. And it worked. Until it didn’t.”

With an eye toward her legacy, Carman went to her uncle with the idea of raising grass-fed beef. “I will never forget what he told me,” she said. “He said, ‘Why don’t you do something people like? What about jerky?’”

The thing that she knew—and that her uncle didn’t—was that there were people in more urban areas who were willing to pay a premium for healthy food. “He had no context,” Carman said. “It’s a paradigm shift.”

While Carman had been around cattle her whole life—and the animals she is raising are direct descendants of the Herefords Weinhard originally brought to the ranch—she had no idea how to finish the animals on grass, since much of that knowledge had been lost in the industry’s rush to finish cattle faster on grain in feedlots.

Carman began to research and implement a practice called holistic management, which is based on the idea that grass is your crop, and a portion of it needs to go back into feeding the land and the soil microbes. A tool of regenerative agriculture, holistic management integrates social, economic, and environmental factors to help the farm or ranch succeed economically, improve the health of the land, and provide local communities more nutritious food.

“Our neighbors are still grazing [their pastures] into the ground with this idea that if you’re not grazing it, you’re wasting it,” Carman said. “For us, that is our nutrient base that we’re putting back into the ground. We’re going to get more productivity by leaving more behind.”

As for her uncle’s reaction to the changes he’s seen since she came back 15 years ago? Carman said he’s now her biggest fan.

“If you come to the ranch, he’ll say, ‘You would not believe the root systems in these grasses,’” she said. “He didn’t see the vision [before], and now I think he does.”

Blazing a Trail Toward a Robust Regional Food Economy

Initially Carman and her husband sold beef in shares, where customers would commit to buying a half, quarter, or eighth of a carcass. They were eventually joined by a neighbor in Wallowa, fellow grass-fed beef rancher Jill McClaran of McClaran Ranch, and they were able to start supplying wholesale clients including Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) in Portland, and Bon Appétit Management Company (an on-site restaurant company, since acquired by London-based Compass Group).

“We slowly started building up this little business,” Carman said. “We raised cattle, finished them on grass, processed them, owned the meat, arranged for distribution through different entities to get the meat out, and then we froze it. It was super tight, but we were kind of scraping by.”

After a customer chipped a tooth on a piece of bone that made it through the grinder at the processing plant and sued, Carman created two LLCs to reduce her liability. Then she took on investors in 2017 to expand her reach. The additional capital allowed Carman to work with larger wholesale accounts such as New Seasons Market, a chain of West Coast grocery stores. Working with a core group of six like-minded producers with ranches from Oregon to Nevada, she is able to supply meat year-round.

“Our purpose in the world is to prove out this model where you can do it the right way,” Carman said of her producers, who agree that building soil is a primary focus, “with layers of values that we’re living toward.”

A woman in the male-dominated field of ranching, Carman notes that women constitute much of her team: she employs a woman ranch manager and director of business development; she has partnered with other women ranchers like McClaran to supply wholesale clients; women serve on the Carman Ranch board and comprise half her investors; and she considers women to be among her most innovative customers.

The model Carman has built so far has already proved an inspiration to other Northwest producers looking to scale up their businesses. Ecotrust’s Oborne said that much of what the nonprofit built at the Redd on Salmon Street, a development designed to support local food enterprises and scale a more robust regional food economy, was based on the work Carman has done.

“Many other regenerative farms and ranches in rural Oregon and Washington are now following in her footsteps and building their businesses in the Pacific Northwest thanks to the trail Cory has blazed,” Oborne said.

Hillary Barbour, director of strategic initiatives for Burgerville, a restaurant chain based in the Pacific Northwest, said its journey with Carman began in a pasture on Carman’s property, when she pulled a chunk of cover crop from the ground, held it triumphantly above her head, and said, “You see, we’re soil farmers!”

Barbour said her company believes Carman’s commitment to soil, human and animal health, and maximizing the value of production for the regional economy aligned with Burgerville’s vision for the future, cementing the relationship going forward.

Beef That Brings It All Together

Calling grass-fed beef “an elegant nexus of all of the issues,” Carman believes that cattle are a necessary component of fertility for every cropping system. That’s because the bacteria in the rumen of the cattle makes what she refers to as “the soil/food web” more vibrant. When we harvest the cattle, we harvest the micronutrients out of the soil, she said.

“The soil/food web needs to be totally functional to get the micronutrients, [and] that’s what we’re missing in our food right now,” she said.

It’s not only that there’s a better fatty acid profile in grass-fed beef, Carman said of studies showing that grass-fed beef is higher in omega-3 fats, vitamin E, beta-carotene, and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). She points to what she calls the human health epidemic of chronic illness and disease, believing that it’s related to how incredibly degraded the soil is from overuse of fertilizers and other industrial practices.

Saying that grass-fed beef is an important catalyst that brings farmers and ranchers together, Carman feels that it’s a place to start the conversation about regenerative agriculture and rebuilding the food system.

“The push is always for any brand to go national,” she said. “Instead, we need to think about production on a regional basis and build out and support appropriately scaled infrastructure. That’s where you can really have the magic.

“Those are all the things we’re trying to prove out with our little model.”

Read more of my articles for Civil Eats, including a profile of Oegon dairy farmer Jon Bansen, and an examination of the damage that factory farm dairies have done to communities in Oregon and around the country. Photos of Cory Carman copyright Nolan Calisch; photos of cattle and sign by John Valls; used courtesy of Carman Ranch.

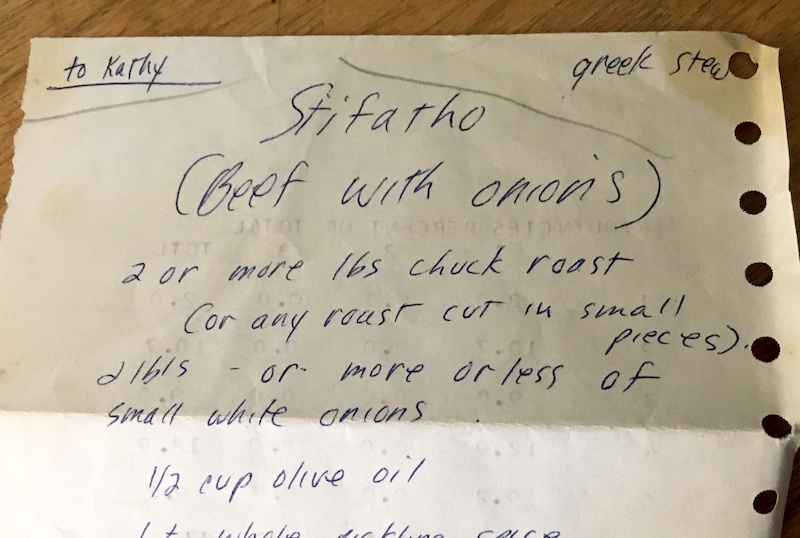

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

If you’re interested in what’s happening in large-scale meatpacking plants,

If you’re interested in what’s happening in large-scale meatpacking plants,  Kalapooia has nearly perfect marks on its annual food safety audits, and on a comprehensive animal welfare audit. Built by Reed Anderson (right, center) to process his own Anderson Ranch lambs, Reed also processes cattle for a few companies, including Carman Ranch. Reed’s son Travis oversees day-to-day operations, and I’ve worked with Pete, Kalapooia's plant manager, for over a decade. The Andersons think of their processing plant as a family business, an ethos that extends to include their staff and customers. Anderson Ranch employs fewer than 50 people, and they took the safety of their workers seriously early on in the COVID outbreak, in part because Pete and Travis work side-by side on the line with their employees. They already required protective clothing, and their small size allowed them to create distancing more easily and effectively than larger plants.

Kalapooia has nearly perfect marks on its annual food safety audits, and on a comprehensive animal welfare audit. Built by Reed Anderson (right, center) to process his own Anderson Ranch lambs, Reed also processes cattle for a few companies, including Carman Ranch. Reed’s son Travis oversees day-to-day operations, and I’ve worked with Pete, Kalapooia's plant manager, for over a decade. The Andersons think of their processing plant as a family business, an ethos that extends to include their staff and customers. Anderson Ranch employs fewer than 50 people, and they took the safety of their workers seriously early on in the COVID outbreak, in part because Pete and Travis work side-by side on the line with their employees. They already required protective clothing, and their small size allowed them to create distancing more easily and effectively than larger plants.  As we move through this crisis, we’re learning more about the vulnerabilities in our incumbent systems. Affordability in food is important, but saving a few dimes can come at a cost none of us should have to shoulder, including our own health and safety. Across the country, those costs are now coming to light.

As we move through this crisis, we’re learning more about the vulnerabilities in our incumbent systems. Affordability in food is important, but saving a few dimes can come at a cost none of us should have to shoulder, including our own health and safety. Across the country, those costs are now coming to light.

Equally if not more important to Carman, however, is the focus on what she calls the “holistic management” of her land. This involves constantly moving the cattle and paying careful attention to the rate of growth of the animals and grasses. By this system, the steers select the forages they need to grow and gain weight, and the grasses get clipped, trampled down, and fertilized with manure, resulting in fields that are vibrant—they retain water, resist drought, contain abundant organic matter, which contributes nutrients and carbon, and are highly productive without the addition of fertilizer.

Equally if not more important to Carman, however, is the focus on what she calls the “holistic management” of her land. This involves constantly moving the cattle and paying careful attention to the rate of growth of the animals and grasses. By this system, the steers select the forages they need to grow and gain weight, and the grasses get clipped, trampled down, and fertilized with manure, resulting in fields that are vibrant—they retain water, resist drought, contain abundant organic matter, which contributes nutrients and carbon, and are highly productive without the addition of fertilizer.

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.