Notorious Mega-Dairy Slated to be Decommissioned after Years of Violations

Waaaaay back in 2017, I began writing about the violations at the famously notorious and now-shuttered Lost Valley Farm. It was later sold to the massive Easterday farming operation before that collapsed, as well. In what turned out to be a prescient warning, I quoted an op-ed by Dr. Nathan Donley, a senior scientist in the Portland office of the Center for Biological Diversity, who wrote:

“The new Lost Valley [Farm] operation will generate as much waste as a small city that will be stored largely in open-air lagoons, then disposed of on fields. Without adequate oversight, there can be no question that every time the state approves a new factory farm it will be opening the door to dangerous health risks—not only for workers but for all those families unfortunate enough to have no choice but to breathe the air around those facilities.”

Tellingly, the problems began when the new owner of the former tree farm, Greg te Velde, cleared the land and started construction of the facility before it was even permitted. Despite that big red flag, permits to operate were issued by the state Dept. of Agriculture (ODA) and Dept. of Environment Quality (DEQ).

Originally permitted to milk 30,000 cows, it was considered a state-of-the-art facility, but due to the erratic actions of te Velde, it never came close to housing that number of cows and was closed due to criminal charges against its owner and hundreds of violations of its permits.

In a 2019 post about the subsequent sale of the property, I asked, "Who would be crazy enough to buy a facility that will require millions of dollars to clean up and more millions to install a new irrigation system…with some 47 million gallons of liquid manure still remaining onsite—which one source estimated would fill 71 Olympic swimming pools?"

Well, that turned out to be the Easterday family, who renamed it Easterday Dairy, then pulled the plug on their plans after four years of what can only be called Shakespearian-level drama. A partial list includes:

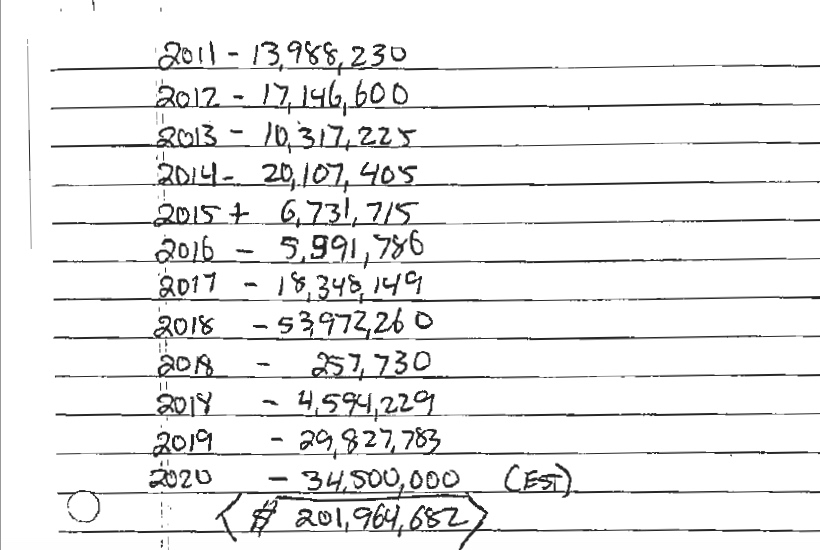

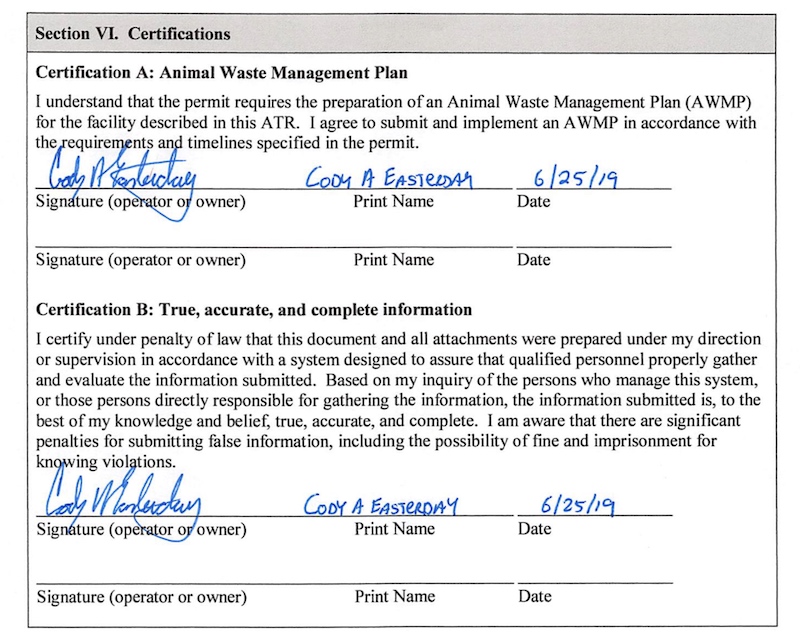

- A massive fraud operation dubbed "Cattlegate" perpetrated by Cody Easterday, scion of the Easterday family enterprises, in which he claimed to be feeding 200,000 cattle owned by Tyson Fresh Meats but, in fact, the cattle existed only on paper and were created to cover up Easterday's losses on the commodities market.

- The death of Cody's father, wealthy cattleman Gale Easterday, who died shortly after the fraud was revealed when he drove his car the wrong way on the freeway near his ranch, running head-on into an 18-wheeler hauling Easterday potatoes.

- Many of the Easterday businesses declared bankruptcy in 2021 and most of the family’s massive farm and ranch empire was auctioned off.

- Cody was sentenced to 11 years in a federal penitentiary in California in 2022 for the fraud against Tyson.

- The ODA handed down a notice of noncompliance in April of 2023 to Cody's son Cole, who was put in charge of the dairy after his father's scam came to light, detailing more than 60 violations ranging from fertilizer spills to irrigation runoff to misapplications of manure on the dairy's property.

- Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) reported in August of 2023 that Cody Easterday and his wife owed the Internal Revenue Service more than $12.5 million in personal taxes, which has issued a lien against their assets.

In early 2023 the Easterdays reached an agreement with the former landowner, Canyon Farms, which is managed by Fall Line Capital, a California-based venture capital firm, in a $14 million lawsuit over how the land was being managed. In mid-August of that year it appeared that Easterday Dairy and Canyon Farms had come to an agreement to sell the property back to the California-based company.

OPB reported that in April of this year, Fall Line had asked to decommission the site as a Confined Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO). According to OPB, "while ODA has granted the request [to decommission the plant], three monitoring wells at the site still show elevated nitrate concentrations above 'background limits' or [has] nitrate levels from before the site was permitted as a CAFO. [The ODA's] Stapleton said the owner is required to bring the wells back into compliance and report monthly samples to ODA."

According to Tarah Heinzen, an attorney for Food and Water Watch, the industrial dairy should never have been permitted in the first place since it is located on a federal Groundwater Management Area (GWMA). "This is an area where people are exposed to unsafe drinking water in part because factory farms and other big ag polluters are contributing nitrates to an already polluted aquifer,” she said. “It [did] not make sense to allow a new source of nitrates into a groundwater management area.”

Even though nitrates are universally acknowledged as extremely hazardous for humans to consume, current nitrate levels in monitoring wells in the GWMA are well over federal maximums. Despite decades of remediation efforts, levels have not shown any decrease and, in fact, the entire aquifer in the area on the banks of the Columbia River is now contaminated. Decades of inaction on the part of regulators has caused residents in the affected counties to sue polluters in federal court.

"The ODA is requiring Canyon Farms to bring the monitoring wells below background limits, yet Oregon has a self-imposed goal to bring nitrate levels in groundwater management areas to seven milligrams per liter or less. The background limits for two of the wells are 15 and 19 milligrams per liter respectively," according to OPB's reporting.

“They need to require that the nitrates are lowered to a health-based limit of seven milligrams per liter, not the so-called 'background levels' that are currently in the plan,” Heinzen said. “We want to see this actually achieve results that are safe for public health and those who might be impacted in their wells down-gradient of this operation.”

The ODA has not yet clarified why it isn't requiring Canyon Farms to bring nitrate levels to the lower levels in its goals.

It seems that Dr. Donley's warning back in 2017was prescient, indeed.

Read "Why I'm Quitting Tillamook Cheese" about mega-dairies in Oregon and "Big Milk, Big Issues for Local Communities" about the real costs to our state of these industrial factory farms.

Photo of Lost Valley cows from ODA; photo of Cody Easterday from Capital Press; photo of Cody at his sentencing from KUOW.

An

An  Then the Statesman-Journal reported that te Velde

Then the Statesman-Journal reported that te Velde  In February of 2018, the Capital Press

In February of 2018, the Capital Press  Love and te Velde issued a dramatic written response to the state's lawsuit, which the Statesman-Journal reported as saying "the injunction would put them out of business, forcing them to lay off 70 workers, euthanize their cows, lose a $4 million per month milk contract, and default on local creditors."

Love and te Velde issued a dramatic written response to the state's lawsuit, which the Statesman-Journal reported as saying "the injunction would put them out of business, forcing them to lay off 70 workers, euthanize their cows, lose a $4 million per month milk contract, and default on local creditors." Despite this, as of the end of March, Tillamook was still buying milk from the dairy, according to

Despite this, as of the end of March, Tillamook was still buying milk from the dairy, according to  "The state’s settlement barely requires more than compliance with the permit already in place—it’s a status quo deal that lets Lost Valley off the hook. The Governor and ODA should have continued seeking to close the operation, which they should never have approved in the first place,' said Tarah Heinzen, staff attorney with

"The state’s settlement barely requires more than compliance with the permit already in place—it’s a status quo deal that lets Lost Valley off the hook. The Governor and ODA should have continued seeking to close the operation, which they should never have approved in the first place,' said Tarah Heinzen, staff attorney with