Solving Big Problems in Small Ways: Josh Volk of Slow Hand Farm

"Slow Hand Farm exists to fundamentally address very large problems

[with our food system] in a very small way, with the understanding that

it's not just one big change that will fix things, but lots and lots

of small changes all working together."

Josh Volk is a farmer who doesn't own farmland, a consultant without a suit, an expert on farm machinery who prefers to build tools himself. He's also a bike racing enthusiast, a teacher, a writer and the author of books on farming and farm tools.

Volk is tall and lean, with a shock of reddish-brown hair that's usually covered with a variety of colorful knit or biking caps in winter or a broad-brimmed straw hat in summer. As is the case with many farmers, when he talks with you he tends not to look at you but out over the landscape, speaking in a cadenced, thoughtful manner that's echoed in his writing.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering.

"I went to engineering school and got a degree in mechanical engineering because I wanted to know how things worked, and I wanted to build bicycles," he writes in his blog. While working in a high tech factory designing tools, he began reading the work of John Jeavons, cofounder of the group Ecology Action and the father of the modern biointensive gardening movement.

Volk started applying his interest in learning how things work, which had served him well in his engineering pursuits, to the problems of producing food. He volunteered at the East Palo Alto Historical and Agricultural Society, a mostly Black and Hispanic organization that was a driving force in lifting up a very poor community through community gardens, reconnecting it with a utopian agricultural past.

Josh is a connector in the farmer community. It’s rare to meet a farmer who doesn’t know Josh or hasn’t heard of him.

Though there are only remnants left today, the Society had a visionary plan for maintaining the integrity of the existing community by expanding open space for small urban agriculture, bringing jobs, job training and economic benefits for its residents.

Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.

Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.

He founded Slow Hand Farm in 2008, as he said, "to fundamentally address these very large problems [with our food system] in a very small way, with the understanding that it's not just one big change that will fix things, but lots and lots of small changes all working together." It was located on leased land on Sauvie Island and allowed Volk both to be a farmer and to continue his consulting work on projects from small gardens to farms with hundreds of acres of production, focusing on small, diversified vegetable growing for direct markets.

"Josh is a connector in the farmer community. It’s rare for me to meet a farmer who doesn’t know Josh or hasn’t heard of him," said Shawn Linehan, a Portland photographer who's known Volk for two decades. "He’s invaluable to our community and totally deserves acknowledgement for the role he's played in helping farms get started and connecting farmers to each other."

In 2013 Volk folded Slow Hand Farm into Our Table Cooperative in Sherwood. Founded by Narendra Varma, a former Microsoft executive who subsequently developed an interest in permaculture and biodynamic agriculture, Our Table describes itself as "a multi-stakeholder cooperative composed of three different interests along the food production chain: workers on our farm, regional producers, and consumers."

In 2013 Volk folded Slow Hand Farm into Our Table Cooperative in Sherwood. Founded by Narendra Varma, a former Microsoft executive who subsequently developed an interest in permaculture and biodynamic agriculture, Our Table describes itself as "a multi-stakeholder cooperative composed of three different interests along the food production chain: workers on our farm, regional producers, and consumers."

After three seasons with Our Table, Volk began working with Matt Gordon at Cully Neighborhood Farm in Northeast Portland. A unique partnership founded in 2010 between Trinity Lutheran Church and Gordon, it was driven by the values of delicious, healthy food, a healthy soil ecosystem, neighborhood-level sustainability and community self-reliance. Volk took over the management of the nearly one-acre property in 2018 when Gordon left to run the education programs for Rogue Farm Corps.

He’s proving that a farm doesn’t need to be big to be profitable.

As we try to change the food system, more people need to understand that

scaling-up operations is not the only game out there.

Cully Neighborhood Farm offers subscriptions to a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture), with shares available in the spring, summer and fall seasons, and Volk plans to offer a winter share in 2023. He's expanded the traditional CSA model by offering free pick-your-own herbs, cut flowers and vegetables in season, as well as access to a large collection of seasonal recipes from Katherine Deumling of Cook With What You Have and an onsite farm stand to supplement subscriber's shares.

Volk's first book, Compact Farms, written in 2015, showcases 15 successful farms that are examples of how farms of five acres or less can be sustainable, manageable, and productive.

"Most how-to farming books will discuss the biology, management and/or tool part of growing veggies, but fail to acknowledge the importance of the farm’s overall set-up," writes Jean-Martin Fortier, founder of The Market Gardener Institute. "He’s also proving…that a farm doesn’t need to be big to be profitable. As we try to change the food system, more people need to understand that scaling up operations is not the only game out there."

"Most how-to farming books will discuss the biology, management and/or tool part of growing veggies, but fail to acknowledge the importance of the farm’s overall set-up," writes Jean-Martin Fortier, founder of The Market Gardener Institute. "He’s also proving…that a farm doesn’t need to be big to be profitable. As we try to change the food system, more people need to understand that scaling up operations is not the only game out there."

Volk's most recent book, Build Your Own Farm Tools, is a collection of the tools he's designed and built for use on his small farm projects, beginning with the basics of setting up a workshop, with plans for 15 tools, including designs for drip irrigation and how to set up spreadsheets for collecting important planning, planting, and market data.

"I’ve encouraged him to patent his tool ideas, but he doesn’t seem keen on the idea," said Linehan. "He thinks the designs should be open source, which speaks to his philosophy about helping others."

That sentiment is echoed by Lane Selman of the Culinary Breeding Network, who calls Volk one of the most collaborative people she knows. "Josh is a giver; he's willing to share everything," Selman said. "He doesn't hoard information but believes in putting it out into the world. He really believes in collaboration rather than competition."

At Cully, Volk has been able to expand on his commitment to environmental and social justice issues by building a small, contained, collaborative system in the community, one that's not built on an economic system that demands continuous growth, with winners and losers.

"When systems get too complicated, there's a lot to tease out," Volk said. "Small businesses, including small farms, are on the whole much more beneficial to the community, the environment and people's lives."

All photos courtesy Shawn Linehan.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

When I wrote recently about

When I wrote recently about  With thicker-skinned citrus like oranges and lemons it'd be best to just use the outer peels, since their pith can be bitter, though with thinner-skinned fruit like Meyer lemons and tangerines (and their small round cousins) you can use the whole peels. And of course I'd recommend only using organically grown citrus, since a wide variety of toxic chemicals and sprays are used on conventionally grown citrus trees and fruit.

With thicker-skinned citrus like oranges and lemons it'd be best to just use the outer peels, since their pith can be bitter, though with thinner-skinned fruit like Meyer lemons and tangerines (and their small round cousins) you can use the whole peels. And of course I'd recommend only using organically grown citrus, since a wide variety of toxic chemicals and sprays are used on conventionally grown citrus trees and fruit.

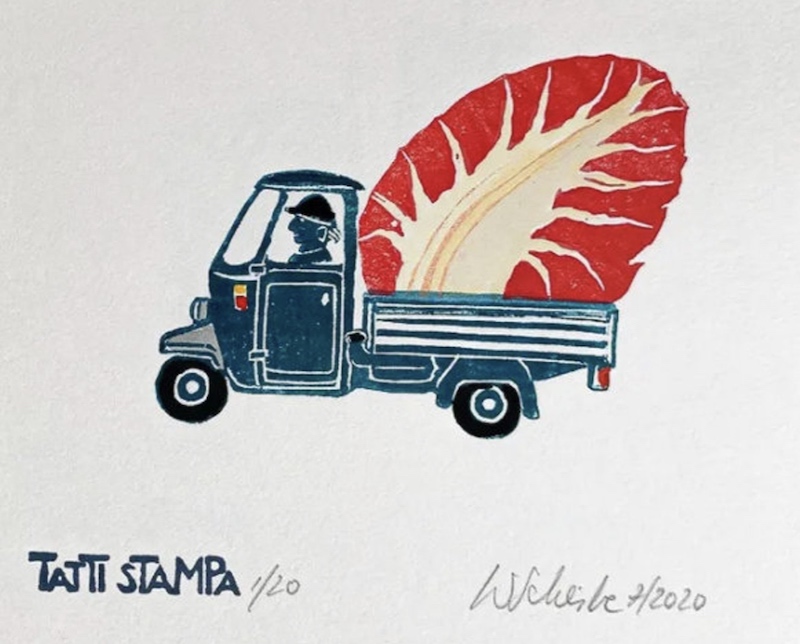

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family.

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family. So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.

So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.

One day it struck me that I was wasting a heck of a lot of perfectly fine fruit juice, not to mention zest, that could be used in cocktails, desserts, salad dressings and any number of other recipes. You know the ones, where they call for a teaspoon of juice or a pinch of zest or a wedge for garnish, only requiring a portion of the whole.

One day it struck me that I was wasting a heck of a lot of perfectly fine fruit juice, not to mention zest, that could be used in cocktails, desserts, salad dressings and any number of other recipes. You know the ones, where they call for a teaspoon of juice or a pinch of zest or a wedge for garnish, only requiring a portion of the whole.

"We’re happy to announce that after many months, the debut of their full-service meat and seafood counter at Providore is here," said Kaie Wellman, co-owner of Providore along with her husband, Kevin de Garmo and their business partner, Bruce Silverman. "The 'protein' corner of the store has been transformed into a mecca for those who want to work closely with their local butcher and fishmonger to source top-quality, small-farmed meat and sustainably caught seafood."

"We’re happy to announce that after many months, the debut of their full-service meat and seafood counter at Providore is here," said Kaie Wellman, co-owner of Providore along with her husband, Kevin de Garmo and their business partner, Bruce Silverman. "The 'protein' corner of the store has been transformed into a mecca for those who want to work closely with their local butcher and fishmonger to source top-quality, small-farmed meat and sustainably caught seafood." A huge problem with our food system is that shoppers are often misled about what they're buying. Tilapia, a common farmed fish, is mislabeled as more expensive snapper—

A huge problem with our food system is that shoppers are often misled about what they're buying. Tilapia, a common farmed fish, is mislabeled as more expensive snapper—

Calling Providore's partnership with these two purveyors a "perfect marriage," Wellman added that "their sustainability standards are unmatched anywhere. These guys walk their talk."

Calling Providore's partnership with these two purveyors a "perfect marriage," Wellman added that "their sustainability standards are unmatched anywhere. These guys walk their talk."